ZEISS microscopes support assisted reproductive technologies

In an average class of 30 children, there is one child who was not conceived naturally. Artificial insemination is the only way for some couples to have their own child. Conventional in vitro fertilization (IVF), also known as test tube fertilization, is regarded as the most well-known procedure in assisted reproductive technologies. In this process, the woman’s fertile eggs are combined with the man’s sperm cells in a small petri dish. Spontaneous fertilization takes place. If the eggs are fertilized there, divide, and continue to develop normally, up to three fertilized eggs are reinserted into the woman’s uterus about 24 to 48 hours later (embryo transfer). In intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), a single sperm is injected into the prepared egg cell using a micromanipulator while being observed under a microscope.

Oocyte with Zona pellucida imaged with ZEISS Axio Vert.A1 (PlasDIC)

Oocyte with Zona pellucida imaged with ZEISS Axio Vert.A1 (PlasDIC)

A hot topic for more than 170 years

J. Marion Sims began working on artificial insemination as early as 1845. He experimented on African and American slaves in the United States. Together with gynecologist Patrick Steptoe, Robert G. Edwards later helped make the first successful birth of a child through artificial insemination possible – Louise Joy Brown was born in England on July 25th, 1978.

Today, the procedure is widely used around the world and has already helped millions of infertile couples have their own child. There are currently over 20 fertility centers in Switzerland, over 30 in Austria, and 130 in Germany.

Visiting the fertility center

“Success and safety are our focus – and for the procedure to be as minimally invasive as possible. There’s nothing better than when a woman becomes pregnant naturally after the first consultation because her mind is relaxed. The greatest feeling of success is when we have to intervene as little as possible,” says Felix Roth of Fiore.

Fiore is a private institute for reproductive medicine and gynecological endocrinology with a total of four centers in Switzerland. Approximately 400 procedures are performed annually at the main center in St. Gallen and the success rate is extremely high. Three laboratory technicians and a manager ensure that everything runs smoothly. Fiore has recently started using the inverse light microscope ZEISS Axio Observer equipped with Narishige manipulators and a laser system.

Felix Roth of Fiore in the lab using ZEISS Axio Observer equipped with Narishige manipulators and a laser system.

Felix Roth of Fiore in the lab using ZEISS Axio Observer equipped with Narishige manipulators and a laser system.

Their range of services includes fertility assessment, hormone therapy, insemination, IVF, ICSI, TESE (testicular sperm extraction), cryopreservation, psychosomatic consultation, and microendoscopic reconstructive surgery.

However, Fiore is not alone in opting for ZEISS as it is also the brand of choice for many other centers.

The Kinoshita Ladies Clinic near Kyoto in Japan has also recently acquired ZEISS equipment to carry out artificial insemination. Two ZEISS Axio Observer 3 microscopes, four ZEISS Stemi 508 stereomicroscopes, six ZEISS Axiocam ERc 5s cameras controlled via ZEISS Labscope, and a ZEISS Primo Star microscope assist Dr. Kinoshita in his daily work. The young doctor only opened his practice last August.

Dr. Kinoshita working with ZEISS Axio Observer – just one of the many ZEISS microscopes at his clinic.

Dr. Kinoshita working with ZEISS Axio Observer – just one of the many ZEISS microscopes at his clinic.

Since 2015, a clinic called the Family Planning Center for Pushkin District has been operating in St. Petersburg in cooperation with the Optec Group Moscow, a ZEISS sales and service partner. The joint advisory center for reproductive medicine is dedicated to IVF professionals.

How is artificial insemination carried out?

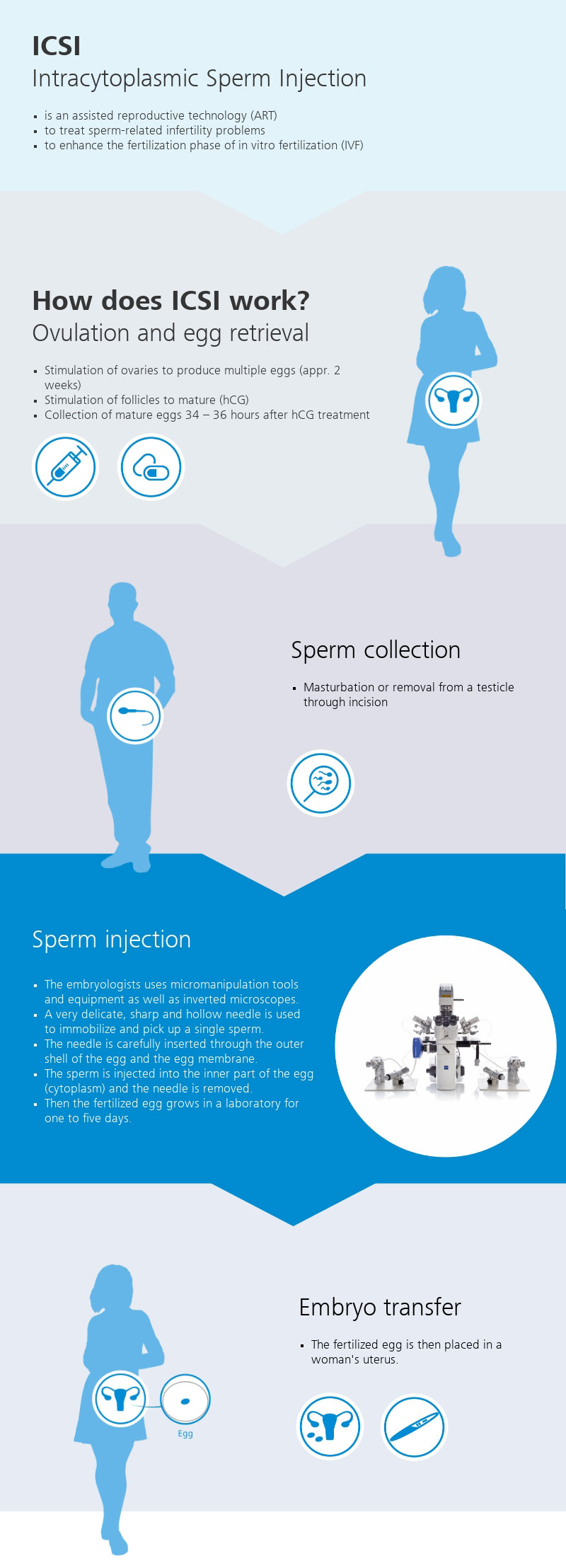

The first step is a consultation with psychologists that lasts at least an hour. This is followed by hormone treatment. The peptide hormone HCG triggers ovulation and ensures that several eggs mature simultaneously. During a normal cycle, a woman develops one or two eggs. Hormonal stimulation increases the probability of pregnancy, yet sometimes the response to stimulation is delayed. Other women, however, do not react at all or are over-stimulated meaning they can produce up to 20 eggs. The quality of the eggs then decreases and the risk of harmful effects increases. The attending physician’s experience and constant ultrasound monitoring play a crucial role.

Ovulation occurs about 37 hours after hormone treatment. The eggs are collected under local or general anesthesia. The laboratory team then transfers them to the stereomicroscope on the preheated, sterile workbench. The eggs are “washed” and the growth culture is added, then they are incubated. Approximately two hours after collection, enzymes are used to remove the protective layer from the egg so that the needle can penetrate more easily. The egg cell is then either frozen or transferred to special petri dishes with microdroplets. In the next step, the laboratory staff adds the sperm. Now, either the sperm fertilize the eggs independently (IVF) or the laboratory staff supports this process (ICSI).

About 40 hours after hormone treatment, the time is right for ICSI. By this time, the egg’s meiotic spindle has already formed. It ensures the correct alignment and separation of chromosomes during meiosis. During the ICSI process, the egg cell is first aspirated with a holding pipette and thus held in place. When doing so, the spindle must not be damaged. The sperm is immobilized, then aspirated into the injection pipette and injected into the egg cell. The sperm cannot inadvertently be sucked out when removing the pipette, but instead must remain in the egg. All available eggs are fertilized in this manner and kept in the buffer medium to keep the pH stable. With the right hormone treatment, an average of eight to ten eggs are obtained per puncture. The fertilized eggs then remain in the incubator for two to five days before being reinserted into the woman.

Microscopy’s role

First, the laboratory technician assesses the morphology and vitality of the sperm using upright light microscopes and prepares what is known as a seminogram. As the transparent sperm components only have a low inherent contrast, these structures can only be imaged directly using phase contrast.

A heated workbench with a ZEISS stereo microscope is then used to prepare and evaluate the eggs:

The heated workbench ensures that the temperature remains stable throughout the process, and stereo microscopes generate three-dimensional images and provide sufficient space for manipulating the eggs.

The heated workbench ensures that the temperature remains stable throughout the process, and stereo microscopes generate three-dimensional images and provide sufficient space for manipulating the eggs.

Finally, the inverse microscope platform ZEISS Axio Observer with micromanipulation and heating plate constitutes the actual ICSI workstation. Several separate incubators complete the set-up to optimally cultivate the fertilized eggs afterwards.

Micromanipulation is a method of manipulating things on a microscopic level using movement smaller than a human is capable of.

Micromanipulation is a method of manipulating things on a microscopic level using movement smaller than a human is capable of.

The challenges

The temperature must be kept constant throughout the process. If the temperature exceeds or falls below 37°C, the risk of damage to the egg and sperm cells increases. The process takes place in a limited window of time – unless the cells are frozen. Sometimes there is only one egg, so you only have one try. Everything comes down to one thing – the workflow cannot be interrupted and the devices must function perfectly. The laboratory cannot afford failures. Individual support and service staff who come quickly when needed play a critical role.

The workflows and techniques have become established over the course of many years. The physician doesn’t have time to learn new techniques. The micromanipulators must be finely adjusted; the doctor must be able to work with them more or less “blindly.” The microscopes should be stable and vibration-free.

“ZEISS Axio Observer is simply a fantastic device. The optics are very, very good – incredibly good,” emphasizes Walter Diethelm of Mikroskop Technik Diethelm, responsible for Fiore as a ZEISS dealer in Switzerland.

Details of individual sperm or details of the zona pellucida on the egg cell can be easily visualized with the microscope.

In very few other fields are the expectations and pressure to succeed as high as

in reproductive medicine. The samples are precious: Only healthy sperm, eggs, and embryos lay the foundation for successful pregnancy. In addition, you have a predetermined period of time in which your workflow must be carried out smoothly. And all of this under controlled conditions, at a constant temperature, and in a sterile environment.

Being easy to operate with excellent ergonomics, ZEISS microscopes support the activities of treating physicians and MTAs. This reduces the time for the individual workflow steps and the precious samples only remain outside the incubator for as long as necessary. Thus, the probability of successful fertilization increases.

More information on ZEISS microscopes for IVF and assisted reproductive technologies

Artificial insemination is an umbrella term for various medical procedures that cause a woman to become pregnant.

The most common method is insemination, in which a man’s sperm is introduced into the woman’s uterus using medical instruments.

Another option is in vitro fertilization (IVF), developed by Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe – fertilization in a test tube. This occurs outside the woman’s body in a glass petri dish – which is why it is called in vitro (Latin for “in the glass”). The egg is removed from the ovary before ovulation. It is then mixed with a nutrient solution and the man’s sperm. The environmental conditions activate the semen – which is necessary for artificial insemination.

ICSI is the next generation of the IVF procedure. The difference lies in the method of fertilization. If the main cause of infertility lies with the man, this procedure is often the only chance for the couple to conceive a child. In this method, a single sperm is injected directly into the egg cell with a very fine pipette while being observed under a microscope. Hormonal stimulation, the removal of mature eggs, and the subsequent insertion of embryos into the uterus are all similar to conventional IVF.

After fertilization, the egg begins to divide. Two and a half days and a few cell divisions later, this still tiny embryo is implanted into the woman’s uterus using a thin needle. Here it further doubles its cells until it has reached a certain stage (blastula). Then the embryo unites with the mother’s tissue and continues to grow – just like a child conceived naturally.