A glimpse into the work of the conservation team at the Imperial Carriage Museum in Vienna

A pleasant calm lies over the conservation workshop of the Imperial Carriage Museum. Matthias Manzini and Isabella Gmeindl are deeply focused on their work. Two spotlights, each approximately 10 cm in diameter, illuminate the areas where they are working with scalpels, cotton swabs, and an incredible amount of patience to remove layer after layer of paint from a carriage. This carriage was built in Budapest in 1895 and once belonged to the Emperor Franz Joseph I. When the monarchy came to an end, the imperial decoration had to be covered up. The carriage continued to be used by the republic.

The bright conservation studio at the Imperial Carriage Museum is large enough to accommodate entire carriages.

You can see right away that the carriage has been painted over from the heavy craquelure on its surface.

Matthias Manzini, who has been working on this carriage since the start of the project over a year ago.

Several layers of paint were added over its many years of use. Analyzing these layers is just one of the conservators’ day-to-day tasks.

Small cracks and fissures can be easily discerned on the painted surface. These may be caused by aging or by the conflicting movements of different layers. These cracks are also known as craquelure.

The day-to-day work of a conservator

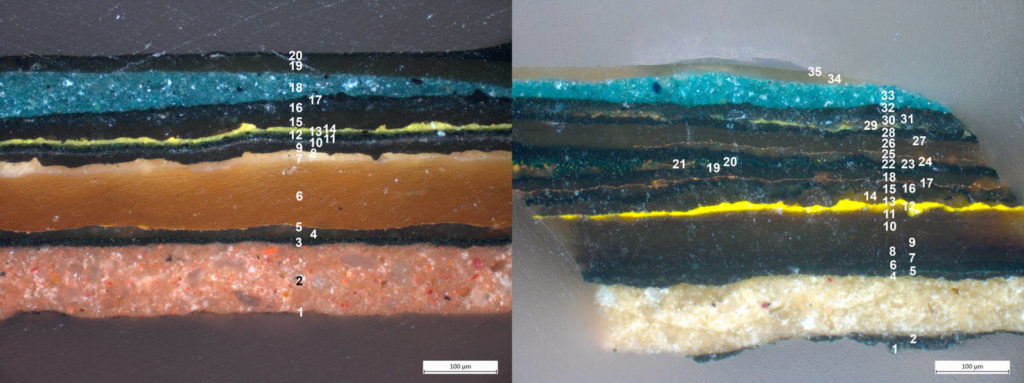

If an object – such as this carriage – is due to be restored, an extensive examination and inventory is carried out first. Microscopic analyses play a big part in this. Details of the various layers can be seen in the transverse sections. To create a section, a sample of just a few micrometers (µm) of material is taken with a scalpel. It is then set in epoxy resin, ground, and analyzed using a light microscope. Up to 37 different layers have been identified using this method.

Transverse sections from the outer hoop of a wheel (left) and the outer carriage body (right). It is clear that the wheels and outer carriage body have been painted and gold-plated multiple times. Images at 200x magnification using differential interference contrast (DIC). Image courtesy of S. Stanek, Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna

Isabella Gmeindl tests each layer with a UV lamp to identify the appropriate solvent.

In the lab, the material sample is analyzed using a scanning electron microscope with an EDX detector to determine the chemical composition of the individual layers. A reddish layer is identified as having traces of iron (Fe) and becomes a clear indicator of rust under the lacquer. The conservators document all their findings carefully. They need to consider how to carry out any restorations and what consequences may be expected to result from an intervention.

Once a detailed conservation or restoration plan has been created, the real work begins. Step by step, the more recent layers are removed using solvents and mechanical removal techniques. More than anything else, this requires patience.

When people ask me what it’s like to restore a carriage, I tell them it’s like scrubbing a ship’s deck with a toothbrush.

Matthias Manzini says with a big grin.

Matthias Manzini in the workshop in front of his restoration project

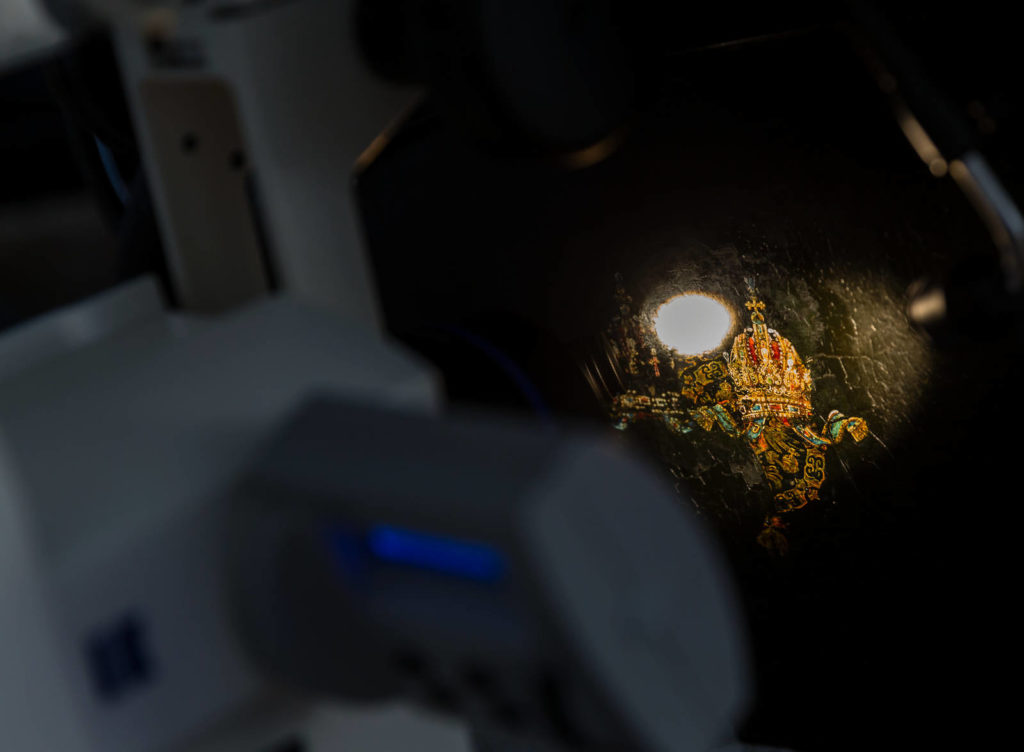

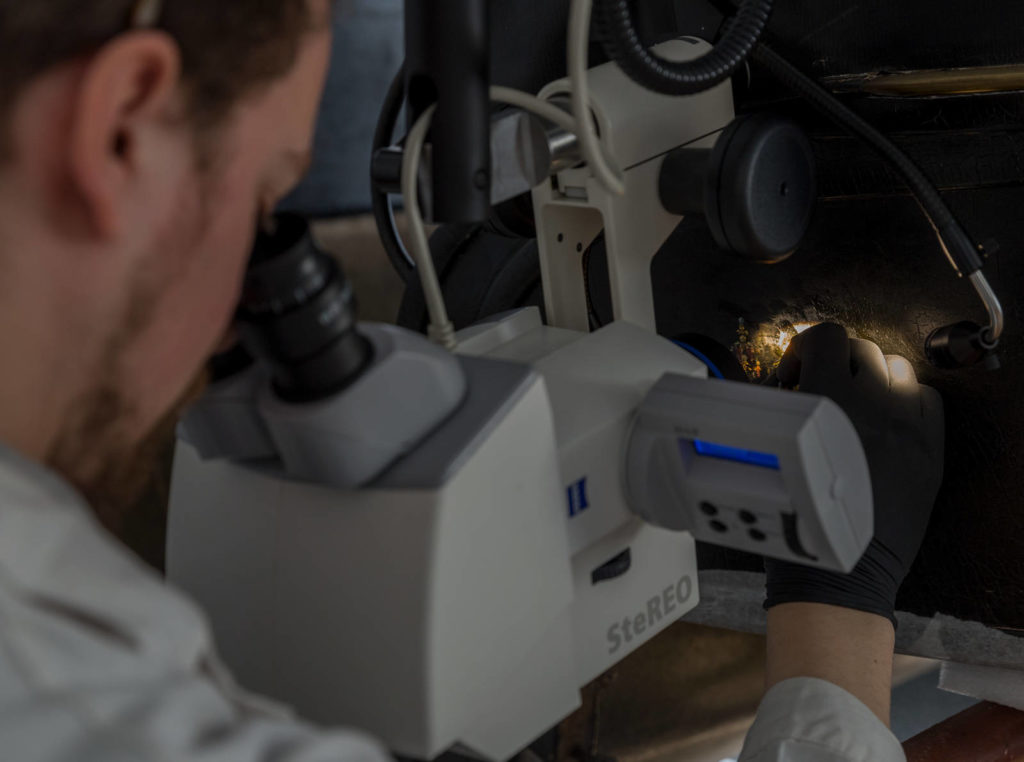

Time pressure is the enemy of every restoration project. Uncovering the coat of arms alone took four weeks – which led to a surprise! Not just one but three coats of arms were uncovered. This provides clear evidence that the carriage was used over a longer period of time during which the “corporate design” was changed. Manzini uses a ZEISS SteREO Discovery.V8 stereo microscope with a floor stand. This allows him to work comfortably on large objects like this carriage while sitting down, to position the microscope at exactly the angle he needs, and to accurately point the light at the area he is working on.

To conservator Matthias Manzini’s surprise, three different crowns became visible when removing the color pigments from the imperial carriage.

Matthias Manzini using a ZEISS stereo microscope.

Being a conservator is both a profession and a vocation

A conservator’s main job is to protect art and heritage artifacts, preserving them authentically and sustainably for future generations. Almost all the item a conservator works on are irreplaceable originals, witnesses to human history. Clearly, these paintings, statues, and similar objects can’t simply be altered without due care and attention.

How do you become a conservator? Matthias owes his calling to his art teacher in high school, who suggested an internship in conservation.

From the age of just 14, Michaela Morelli, a textile conservator at the Imperial Carriage Museum, was able to start learning to embroider, weave, dye, and print fabrics in the upper grades of the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts. A chance encounter helped her on her way; during a bus ride, she met a textile conservator who offered her a one-month trial internship. One month turned into a year and a half, and the foundation for her future career had been laid. After studying in Cologne, she ultimately returned to Vienna.

As a conservator, you use both your head and your hands.

Michaela Morelli, a textile conservator at the Imperial Carriage Museum

She’s hit the nail on the head there; restoration involves a combination of science and craftsmanship. Good conservators need practical skills, artistic sensitivity, theoretical knowledge concerning the fields of art and culture, and technical know-how. They need to be able to identify the age of an object and trace its history. And on top of that, they need a solid expert understanding of chemistry, physics, and microbiology.

Conservators need a comprehensive understanding of all the equipment associated with the artifact.

The Imperial Carriage Museum in Vienna

The work conservators do behind the scenes is the foundation that allows museum visitors to admire the carriages, clothes, and other items on display.

The Imperial Carriage Museum in Vienna comprises multiple collections. Taking care of them requires the full range of professional conservation and restoration activities.

The museum houses vehicles from the Viennese court’s formerly 600-strong fleet of conveyances – from state carriages to baby strollers.

Vehicles from the Viennese court

From the 19th century onwards, the court carriages – which always had right of way over other carriages – were identified by their paintwork in courtly green and gold. The width of the gold stripes on the wheels of the carriage indicated the rank of its passengers.

The stripes on the wheels indicated the rank of the carriage’s passengers.

Until 1918, the countless elegant equipages of the court were an important feature of the Viennese streets. After this date, the court carriages (which were considered historically important even then) were gifted to the Carriage Museum. The utility vehicles were painted over and continued to be used. If they find their way back to the Carriage Museum nearly a century later, like Emperor Franz Joseph I’s carriage from Budapest has, it’s an unparalleled stroke of luck – and a big challenge for the conservators!

Manzini works with a wide variety of materials when restoring carriages.

Gilded wooden structures, glass windows, padded interiors, embroideries, metal traction elements, paintings on the wooden elements: a carriage represents the interaction of a wide variety of materials.

Textiles, varnish, wood, and metal all require very different analysis and treatment methods. He uses UV light or stereoscopic grazing light, with different microscope contrasts if necessary, to view the layers of the craquelure-covered paint surface. The metal composition of the wheels is determined using electron microscopy and EDX detection, and textile fibers are best analyzed using the polarization contrast on a light microscope.

The Emperor’s new clothes

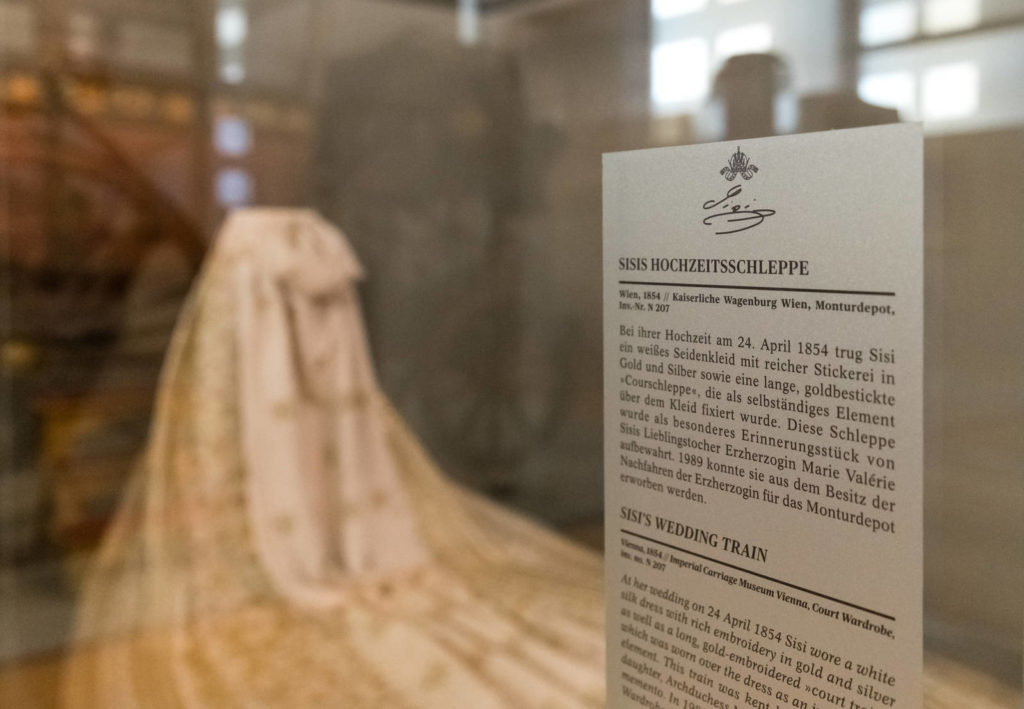

And speaking of textiles – after the collapse of the monarchy, the no-longer-needed liveries of the Office of the Master of the Horses, along with the wardrobes of the Habsburg Orders (the Golden Fleece, the Order of St Stephen of Hungary, the Order of Leopold, and the Order of the Iron Crown), were given to the Kunsthistorisches Museum. These form the core of the Court Robes and Uniforms collection, one of the most important collections of court dress from the 19th and early 20th centuries in the world. The Court Robes and Uniforms collection is being constantly expanded through systematic acquisition activities. The imperial garments are the highlights of the collection, including items such as the train from Empress Elisabeth’s wedding gown.

Sisi’s wedding train is one of the few surviving items of the Empress’s clothing.

Morelli is the textile conservator for the Imperial Carriage Museum and the Court Robes and Uniforms collection. There are a particularly large number of items of clothing alleged to have been owned by Empress Elisabeth – also known as Sisi – in circulation. Assessing whether an item is an original or a fake isn’t easy. With a twinkle in her eye, Morelli points at a pretty chenille dress and explains that it was adjusted for a different, later wearer – one of the Empress’s nieces. Morelli uses the ZEISS Axiolab light microscope with polarization contrast to analyze fibers, assess the condition of the material by age, and to document any damage caused, for example, by moths. With the help of the contrast, she is able to differentiate between linen and flax and is sometimes able to pin down the age of a garment.

Conservator examines royal fabrics.

With plenty to do every day, the conservators have no time to be bored. There are donations to be assessed and existing collections to be conserved. Temporary exhibitions on exciting topics such as the Congress of Vienna, the Empress Sisi, and the Napoleonic Era place Manzini, Morelli, and the collection’s third conservator, Daniela Sailer, in contact with new artifacts – and new challenges – every day.

The Imperial Carriage Museum is located on the grounds of Schönbrunn Palace in the Hietzing district of Vienna and houses over 30,000 objects. Of the roughly 200 vehicles in the Carriage Museum, 101 come from the fleet of the Viennese court, while the others belonged to families that were members of the courtly nobility. The museum, which is part of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, represents one of the most important collections worldwide.

Read Next – More Articles on Museums & Restoration

The Mary Rose – a Unique Glimpse Into Life in Tudor Times